Introduction: The World Beneath the Water Sky

Before stories had names, before seasons were marked with carved shells or chants, there was only the water sky.

That is what the old ones called it, the mirrored vastness of the lake that reflected both moon and cloud, both fish and star. It was neither land nor sea, yet it gave birth to both. It fed the grass that fed the deer, and the snails that fed the ibis. It cradled storms and drank sunlight. Its edges were not drawn on bark or bone. They were known by the way frogs sang, or by the scent of sulfur rising after rain.

Here, the Calusa lived not as owners, but as companions. They did not till the earth in rows or fence it off. Their lives were shaped by fish migrations, by reed bloomings, by the long breath of the lake. What they built, canals, shell mounds, fish weirs, were not scars on the land, but braids in its hair.

This was the inland edge of their watery kingdom, where brackish fingers reached through marsh and mangrove to touch the sweet water of Oki. Though the heart of the Calusa lay along the coasts where tides obeyed the moon, this place was sacred. It was the basin where thunder spirits hid in the wet season, and where birds danced for no eyes but the wind’s.

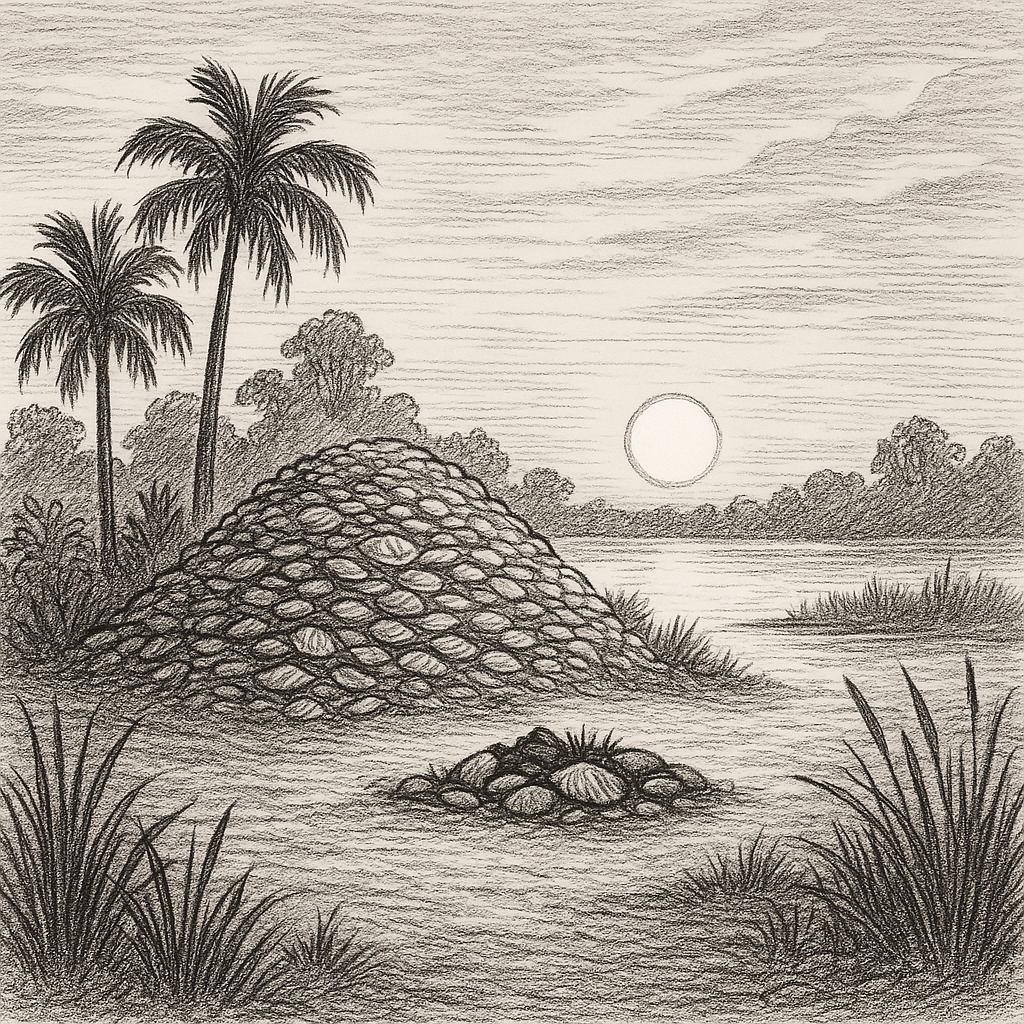

Here stood a shell mound ringed by sawgrass, its summit dry through the longest rains. Built by hands whose names were now part of the wind, it served both as hearth and home to a small clan within the reach of the coastal chiefs. Their lives followed the rhythm of three moons that signaled change, a time of gathering, proving, and offering.

The mound rose in a wide crescent, its arms open toward the rising sun. Within that curve, life followed the turning of sky and water. The people here knew how to listen. The wind that passed through reeds could carry a warning. A pause in bird calls could mean that alligators were moving through the floodways. A single dragonfly circling low to the ground might mean the lake was warming and the turtles would climb ashore soon.

Each family on this mound traced its lineage through water. Children learned to swim before they could run. Language flowed like rivers, looping and returning in stories told by firelight and silence. Bones of fish and birds were never wasted, always returned to the edge with thanks. Death was not a leaving, only a shifting current.

The lake was alive. It was not a backdrop or a provider to be used, but a breathing presence. When it grew angry, they listened. When it gave abundantly, they fed the birds first. They said the lake kept memory better than the old people. What you put in, it returned. What you forgot, it remembered.

This mound belonged to a family of five. Natta, the father, tended the weirs and fish traps. He was a net-maker and a silent reader of water. His work was not seen, only felt in the full baskets each morning and the quiet hum of canoes sliding across still water. He taught his son Kalo how to track fish by watching the breath of the lilies and listening for the twitch of tails beneath silt.

Suala, the mother, was the healer and keeper of moon rites. She gathered roots, dried flowers, and carved sacred seeds. Her medicine was not just for the body, but for the balance between lake and life. She wrapped her bundles with strands of woven reed and whispered to the water spirits before each boil. People came from nearby hammocks to sit by her fire and sip from her bitter gourds.

Their son, Kalo, had nearly reached his proving age. He was tall already, with strong hands from carving and paddling, but his voice still caught when speaking before elders. He watched storms with stillness and spent too much time by himself in the shallows. His journey, the rite that would name him fully in the eyes of the clan, was approaching. Soon, he would leave alone and return with a token chosen not by him, but by the lake.

Tika, their younger child, knew no fear of mud or snake. She had not yet seen ten wet seasons, but her thoughts moved like clouds, light, fast, and hard to hold. She told stories to crabs and left gifts in old turtle nests. She spoke of dreams that made the elders stop what they were doing and look at the sky.

Then there was Elder Paako, Suala’s uncle and the oldest voice on the mound. He no longer traveled to trade camps or fished with the others, but he carved. Every day, he sat beneath a woven awning and shaped driftwood into paddles, birds, or hollow flutes. He had seen forty wet seasons, maybe more. His eyes did not always follow movement, but when he spoke, people listened. His voice was not strong, but the wind carried it.

When the storms came, they came from the south and east. When the rains came, they filled the canals and flooded the paths. But the mound held. Always the mound held. It had been built that way, layer upon layer of shell and ash, each one pressed down with story.

At night, the people gathered in the center of the crescent. The fire pit burned low, and the air smelled of fish skin, burning palmetto, and dried citrus peel. Songs were not always sung with words. Sometimes they were carried only by drums and breath, by feet stomping soft rhythms into the shell-packed ground. Overhead, the sky showed no end. The stars had their own trail, moving in slow procession, the same path followed by the eels and the cranes.

Far to the east, they said new sounds sometimes reached the coast. Large canoes with walls of tree and strange sails had been seen. No one here had seen them, not yet. Their arrival belonged to another moon.

This is the moon before that one. This is the time of balance, of offering, of memory. It is the turning of three moons in the life of one family, their mound, and the lake that remembers everything.