That night, the fire was low and steady. The smoke lifted straight, then curled in tight spirals. No one spoke. The stars blinked in the dark above like scattered shells on black sand.

Paako sat with his legs crossed, his back straight despite the years. His voice came slow and dry, like wind sifting through reed.

“There was once a boy,” he began, “born on a mound like this one, in a cycle not far from now, but too far to name. He was small and curious. He followed turtles, he mimicked birds, and he liked to stand in shallow water and feel the minnows nip his ankles.”

Tika leaned closer.

“He asked many questions,” Paako continued. “Most were about the lake. Why does it hide the stars when it rains? Why do the fish sleep with their eyes open? Why does the wind stop just before the storm?”

“The elders grew tired of answering, so they told him to ask the lake directly. They said, ‘Go be still. The lake will answer in its own way.’ So he did.”

He paused, letting the wind shift.

“One morning, the boy paddled alone into the center of the lake. He did not take food, or net, or firestarter. Only his questions. When he reached the stillest place, he stopped paddling. He sat cross-legged in the canoe, closed his eyes, and did not move.”

Tika held her breath.

“The birds circled overhead and left. The frogs sang, then stopped. The sun rose, then fell. The boy stayed. No one came for him. The elders said, ‘This is what he asked for.’ The parents said, ‘This is what the lake asked of him.’”

He looked at Kalo as he spoke the next part.

“On the third night, the canoe returned. Empty.”

Suala lowered her head slightly. Kalo’s hands were folded in his lap.

“No one spoke of it. The mound went on. Fish were caught. Rain fell. Children played. But some nights, in the season of smoke, when the fire burned blue at its edges, someone would see a shape walking at the water’s edge. Thin, and still, and always listening.”

“He never came back?” Tika asked.

“Oh, he did,” Paako said, tapping the side of his head. “Not in body, but in remembering. Some say he became part of the lake. Others say he still wanders the trails under the surface, speaking in the language only fish and wind can understand.”

He leaned forward, eyes brighter now.

“But this is what matters. The boy did not drown. He did not vanish. He became part of the pattern. The lake keeps what listens.”

He poked the fire with a blackened stick. Sparks lifted into the air.

“Some say he waits, even now, for another who will ask the right question.”

The fire cracked softly. No one moved.

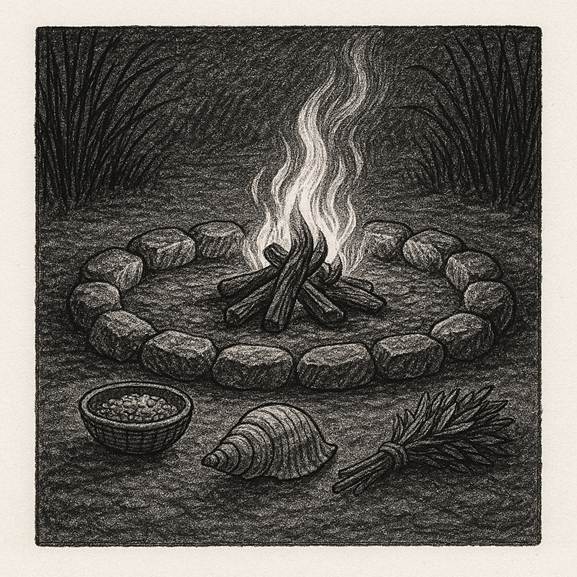

**Fire Ring with Offerings**

The sky changed color before the lake did.

It was not a sudden thing, not a storm. The air turned the color of scraped limestone and stayed that way, even at midday. Light spread without warmth. Shadows lost their edges. Everything moved slower, like breath held too long.

This was the month of smoke, of gathering fires, of harvest pulled not from earth but from water and sky.

Kalo rose each morning before the others. His rite had ended, but something had remained with him. He walked the mound differently now, pausing more often, staring not at things but through them. He watched the birds fly in new patterns. He tracked the movement of snails as they climbed higher than usual along the trunks. He did not speak of the dream again.

Tika followed him one morning and asked if the white bird had wings again.

“I don’t know,” he said. “It’s not a bird anymore.”

Suala listened to the wind each evening. She stood near the canal and burned crushed pine needles on a flat stone, waiting for the smoke to rise in a steady line. It hadn’t in seven nights. Each time, the smoke curled downward and twisted left, the direction of mourning.

The fish changed too. Natta noticed it first. Their scales dulled, their eyes grew clouded. They swam in erratic loops, and some floated near the surface, as if confused by their own reflection. The traps still filled, but more fish died before the morning.

Paako did not carve.

He sat beside the fire, silent and unmoving, his hands resting on his knees. His last piece of driftwood sat untouched beside him. Tika tried to place it in his lap. He shook his head.

“I have finished,” he said, barely above the wind. “Now I must remember what I forgot.”

Tika looked at Suala. Suala said nothing.

That week, a canoe arrived from the coast.

Not a trader. Not a messenger.

It was a single man, burned dark by sun, thin as a reed, eyes wide and yellow at the edges. He wore no jewelry. His arms bore no shell bands, no clan markings. He did not speak when he came ashore.

He carried no bundle.

He simply walked to the fire and sat.

Natta offered food. The man did not move. Tika offered water. He took it without a word.

Only Paako addressed him directly. “What have you seen?”

The man stared into the fire. “The sky split,” he said. “The trees burned.”

Suala knelt beside him. “From storm?”

“From men.”

His voice was rough. “The boats. They came. But not just boats. Floating walls. Shouting thunder. Trees broken at the base. Water turning dark.”

“Where?” Natta asked.

“Far. Not far enough.”

The man stayed three nights, then left before dawn. No one saw him go.

In the following days, the people of the mound began to gather what they could not carry. Seeds wrapped in bark. Stones used for grinding. Carved records etched onto turtle shells. They did not speak of leaving, but their movements whispered it. Canoes were checked for cracks. Paddles were tied with new leather.

Tika found Kalo that evening at the edge of the canal, staring into the water.

“Are we going?” she asked.

“I don’t know.”

She reached into the satchel slung over her shoulder and pulled out a bracelet. It was the one she had made from cattail and snake grass. “You never took it.”

Kalo tied it around his wrist.

The next morning, the lake changed.

It turned silent, not with peace but with pressure. Birds left the reeds. Even the insects fell quiet. Elder Paako stood once more and placed his unfinished carving into the fire. As it burned, he whispered a name no one recognized.

The flames cracked open the shell of the mound’s stillness.

That night, the people gathered for the shell fire, the rite of final offerings. Not final as in ending, but final as in release. Everyone brought something. A story, a feather, a broken pot. Tika brought a fish scale the size of her palm, one she claimed had fallen from the sky.

Kalo stepped forward last. He held a small clay cup filled with water from the place he had dreamed of. The place where the lake had kept him.

He poured it onto the fire.

Steam rose like breath from the mouth of the lake.

Suala sang then, soft and deep, a sound with no words. The others joined. Their voices blended with the crackle of burning shells and the rustle of reeds in the wind.

In the firelight, the mound no longer looked like a home. It looked like a memory of one.

In the days after the shell fire, the mound became quiet.

Not in mourning, but in preparation.

The fish traps were pulled in. The clay pots were packed in leaf wrap and tied with vine. Suala buried bundles of seed and root near the oldest hearth, marking the place with four oyster shells set in a square. “If we must return,” she said, “this will help the memory find its way.”

Tika helped Paako walk each path one last time. He moved slowly, stopping to place his hand on each marker stone around the outer edge of the mound. He whispered to the wind, to the ground, to something neither child nor bird could hear.

They were not leaving yet. No one had said it. But the lake had.

One morning, a heron fell from the sky. Its wings were whole, but its eyes were wrong, pale and ringed with green. Suala buried it with salt and fire.

Natta sat for hours in the canoe without paddling, just watching the waterline. Kalo joined him once and said nothing. They stayed until the moon climbed high enough to break the silence between them.

“They are near,” Natta said finally.

“I know,” Kalo replied.

The next day, Kalo and Tika walked the trail that led to the outer water. It had once been clear, a route used often for trading. Now it was overgrown, its edges soft, like the land wanted to forget it had ever been open.

Tika stopped near a broken stump and picked up a shell shard shaped like a crescent. “I’ll leave this here,” she said. “So they know someone was kind.”

Kalo said, “Will they care?”

Tika didn’t answer.

Back at the mound, Suala and Paako prepared the final fire. This one was small, made only from dry root and braided moss. It was not for warmth, not for cooking. It was a signal.

As the smoke rose, Kalo noticed it drifted straight upward, clear and true.

“The wind has changed,” he said.

Paako nodded. “So has everything.”

That night, Kalo stood by the canal holding the carved stick from his rite. He dipped it into the water three times, then placed it on the stone ledge beside the fire.

“It is not mine anymore,” he said.

The others gathered without being called. One by one, they placed their offerings around the stick: a dried herb bundle from Suala, a coil of fishbone from Natta, and a smooth flat stone from Tika’s pocket. Paako gave nothing. He only raised his hand and let it fall.

The fire burned low. No one added more wood.

When the embers glowed with their last light, the lake gave one long breath. A ripple passed through the canal, barely touching the bank.

Kalo turned to Tika. “This is how it ends.”

Tika shook her head. “No. This is how it remembers.”